Purpose

Introduction

International travelers encounter extremes of climate to which they might not be accustomed. Exposure to heat and cold can result in serious injury or death, so travelers should prepare themselves with knowledge, proper clothing, and equipment to prevent problems. Environments with wide temperature fluctuation, such as mountains and deserts, present risk for both heat and cold problems (see Adventure Travel chapter). Climate change is expanding the range and severity of exposure to heat across many travel destinations.

Heat-related illness

Risk for travelers

Heat-related illness is most often seen in occupational, military, and competitive sport activities, but it can also occur from recreational activities. Many of the most popular travel destinations are hot tropical or arid areas. Travelers who sit on the beach or by the pool and do only short walking tours incur minimal risk for heat-related illness. People participating in adventure travel with more strenuous activities, like hiking or biking, in hot environments are at greater risk, especially those coming from cool or temperate climates who are not in good physical condition and who are not acclimatized to heat.

Physiology

Unlike in the cold, where adaptive behaviors play a more important role in body heat conservation, tolerance to heat depends largely on physiologic factors. Heat regulation depends on a combination of physical, physiological, and environmental factors. The major means of heat dissipation are radiation and convection (air movement) while at rest and evaporation of sweat during exercise, both of which become minimal when air temperatures are above 35°C (95°F) and humidity is high.

Cardiovascular status and conditioning are the major physiologic variables affecting the response to heat stress at all ages. Two major organ systems are most critical in temperature regulation: the cardiovascular system, which must increase blood flow to shunt heat from the core to the surface while meeting the metabolic demands of exercise; and the skin, where sweating and heat exchange take place. Many chronic illnesses limit tolerance to heat and predispose people to heat-related illness, most importantly, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, renal disease, certain medications, and extensive skin disorders or scarring that limit sweating. Other risk factors are certain medications, very young or old age, high body mass index, and acute infection.

Apart from environmental conditions and intensity of exercise, dehydration is the most important predisposing factor in heat-related illness. Dehydration reduces exercise performance, decreases time to exhaustion, and increases internal heat load. Temperature and heart rate increase in direct proportion to the level of dehydration. Sweat is a fluid containing sodium and chloride. Although it is hypotonic (contains lower concentration of sodium than blood), sweat rates may reach 1 liter per hour, resulting in substantial fluid and sodium loss.

Clinical presentation

Mild

Mild heat-related problems can be treated in the field and usually do not require medical evaluation or evacuation (Table 3.2.1). Treatment for these includes some combination of removal from heat, supine rest for syncope, and hydration, optimally including some salt from fluids or snacks. Rehydration can be achieved by commercial rehydration solutions or a salt solution as described for heat exhaustion. Drinking water and eating a salty snack also is sufficient.

Table 3.2.1: Mild heat illnesses

| Problem | Clinical Findings | Management | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heat cramps | Painful muscle contractions that begin ≥1 hours after stopping exercise and most often involve heavily used muscles in the calves, thighs, and abdomen | Rest and passive stretching of the muscle and gentle massage; rehydration | |

| Heat edema | Mild swelling of the hands and feet during the first few days of heat exposure; more common in women | Resolves spontaneously | Do not treat heat edema with diuretics, which can delay heat acclimatization and cause dehydration |

| Prickly heat (miliaria or heat rash) | Small, red, raised itchy bumps on the skin caused by obstruction of the sweat ducts | Resolves spontaneously, aided by relief from heat and avoidance of continued sweating | Prevent prickly heat by wearing light, loose clothing and avoiding heavy, continuous sweating |

| Heat syncope | Sudden fainting that occurs in unacclimated people standing in the heat or after 15–20 minutes of exercise | Move to shade or cool place; consciousness rapidly returns when the patient is supine; rehydration |

Moderate

Heat exhaustion

Most people who experience symptoms associated with exercise in the heat or the inability to continue exertion in the heat are suffering from heat exhaustion. The presumed cause of heat exhaustion is loss of fluid and electrolytes (primarily sodium, chloride, and potassium), but there are no objective markers to define the syndrome. Mental changes (e.g., irritability, confusion, irrational behavior) might be present in heat exhaustion, but major neurologic signs (e.g., seizures, coma) indicate heat stroke or profound hyponatremia. Body temperature could be normal or mildly to moderately elevated. It is critical to begin cooling measures (Box 3.2.1), as well as rest and rehydration, until the clinical course becomes clear. If mental changes do not improve rapidly and temperature is not elevated, consider hyponatremia (see later in this chapter). Heat exhaustion also can develop over several days in unacclimatized people and often is misdiagnosed as "summer flu" because of findings of weakness, fatigue, headache, dizziness, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

Most cases of heat exhaustion can be treated with supine rest in the shade or other cool place and oral water or fluids containing glucose and salt; subsequently, spontaneous cooling occurs and patients recover within hours. Travelers can prepare a simple oral salt solution by adding 1/4–1/2 tsp of table salt (or two 1 g salt tablets) to 1 liter (33 oz) of water. To improve taste, add a few teaspoons of sugar or orange or lemon juice to the mixture. Commercial sports-electrolyte drinks also are effective. Plain water plus salty snacks might be more palatable and are equally effective. Without cessation of activity and passive or active cooling measures (see later in this chapter), heat exhaustion can progress to heat stroke.

Box 3.2.1

Severe

Severe heat-related illness requires medical evacuation and emergency medical attention.

Heat stroke

Heat stroke is a medical emergency requiring aggressive cooling measures and hospitalization for support. Heat stroke is the only form of heat-related illness in which the mechanisms for thermal homeostasis have failed and the body does not spontaneously restore the temperature to normal. Uncontrolled hyperthermia and circulatory collapse cause organ damage to the brain, kidneys, liver, and heart. Damage is related to duration and peak elevation of body temperature.

Onset of heat stroke can be acute or gradual. Acute (also known as exertional) heat stroke is characterized by collapse while exercising in the heat, usually with profuse sweating. It can affect healthy, physically fit people. By contrast, gradual or non-exertional (also referred to as classic or epidemic) heat stroke occurs in chronically ill people experiencing passive exposure to heat over several days. Victims of both exertional and non-exertional heat stroke demonstrate altered mental status and markedly elevated body temperature.

Early symptoms are like those of heat exhaustion, including confusion or change in personality, loss of coordination, dizziness, headache, and nausea, but these progress to more severe symptoms. A presumptive diagnosis of heat stroke is made in the field when people have body temperature ≥41°C (≥104°F) and marked alteration of mental status, including delirium, convulsions, or coma; even without a thermometer, people with heat stroke will feel hot to the touch. If a thermometer is available, a rectal temperature is the most reliable way to check the temperature of someone with suspected heat stroke; an axillary temperature might give a reasonable estimation. See Box 3.2.1 for additional guidance on managing heat stroke.

Heat stroke is life-threatening, and many complications occur in the first 24–48 hours, including liver or kidney damage and abnormal bleeding. Most victims have significant dehydration, and many require hospital intensive care management to replace fluid losses. If evacuation to a hospital is delayed, patients should be monitored closely for several hours for temperature swings.

Exercise-induced hyponatremia

Hyponatremia occurs in both endurance athletes and recreational hikers due to physiologic mechanisms that result in failure of the kidneys to correct salt and fluid imbalances properly. Excess fluid retention occurs when inappropriate levels of antidiuretic hormone influence the kidneys to both retain water and excrete sodium. Sodium losses through sweat also contribute to hyponatremia.

In the field setting, altered mental status in a patient with normal body temperature and a history of taking in large volumes of water suggests hyponatremia. Excessive water ingestion is also a major contributor to exercise-associated hyponatremia; the recommendation to force fluid intake during prolonged exercise and the attitude that "you can't drink too much" is outdated and dangerous. Prevention includes drinking only enough to relieve thirst. During prolonged exercise (>6 hours) or heat exposure, people should take supplemental sodium. Most sports-electrolyte drinks do not contain sufficient sodium to prevent hyponatremia; on the other hand, salt tablets often cause nausea and vomiting. For recreational athletes, food is the most efficient vehicle for salt replacement. Snacks should include not just sweets but also salty foods (e.g., trail mix, crackers, pretzels).

Symptoms of heat exhaustion and early exercise-associated hyponatremia are similar, including anorexia, nausea, emesis, headache, muscle weakness, and lethargy; hyponatremia symptoms can, however, progress to confusion, seizures, and coma. Hyponatremia can be distinguished from other heat-related illnesses by persistent alteration of mental status without elevated body temperature, delayed onset of major neurologic symptoms, or deterioration hours after cessation of exercise and removal from heat. Where medical care and clinical laboratory resources are available, clinicians can measure the patient's serum sodium to diagnose hyponatremia and guide treatment.

Treating clinicians should restrict fluid if hyponatremia is suspected. If the patient is conscious and can tolerate oral intake, clinicians should give salty snacks with sips of water or a solution of concentrated broth (2–4 bouillon cubes in 125 mL or 1/2 cup of water). Obtunded hyponatremic patients require intravenous hypertonic saline.

Prevention

Clothing

Travelers should wear lightweight, loose, light-colored clothing that allows maximum air circulation for evaporation but also gives protection from the sun (see Sun Exposure in Travelers chapter). In addition, travelers can wear a wide-brimmed hat, which markedly reduces radiant heat exposure.

Fluid and electrolyte replacement

During exertion, fluid intake improves performance and decreases the likelihood of illness. Reliance on thirst alone is not sufficient to prevent mild dehydration, but forcing a person who is not thirsty to drink water increases the risk of hyponatremia. During mild to moderate exertion, electrolyte replacement offers no advantage over plain water. A person exercising for many hours in the heat should replace salt by eating salty snacks or by lightly salting mealtime food or fluids. Salt tablets swallowed whole can cause gastrointestinal irritation and vomiting; tolerability can be improved by dissolving tablets in 1 L (approximately 4 cups) of water. Using urine volume and color to monitor fluid needs is most accurate in the morning.

Heat acclimatization

Heat acclimatization, a process of physiologic adaptation that occurs in residents of and visitors to hot environments, is highly effective at decreasing the impact of heat stress and reducing heat illness. It results in increased thermal tolerance, improved muscle and cardiac function with decreased energy expenditure and lower rise in body temperature for a given workload, and enhanced skin blood flow and sweating response. Only partial adaptation occurs from passive exposure to heat. Full acclimatization, especially cardiovascular, requires 1–2 hours of exercise in the heat each day. With a suitable amount of daily exercise, most acclimatization changes occur within 10 days. Decay of acclimatization occurs within days to weeks if there is no heat exposure.

Physical conditioning

Physically fit travelers have improved exercise tolerance and capacity in any temperature but benefit additionally from heat acclimatization. If prior acclimation is not possible, clinicians should advise travelers to limit exercise intensity and duration during their first week of travel. Travelers also should try to conform to the local practice in most hot regions and avoid strenuous activity during the hottest part of the day.

Cold-related illness and injury

Risk for travelers

Cold illness and injury education should focus on prevention. The major forms of heat loss in descending order of cooling rate are conduction (water immersion, wet clothing), convection (wind), and radiation (clothing, insulation). Understanding this will guide appropriate gear and clothing choices. Most important in cool environs is to remain dry by layering and quickly changing any moist clothing to avoid cold injury and exposure.

Clinical presentations

Hypothermia

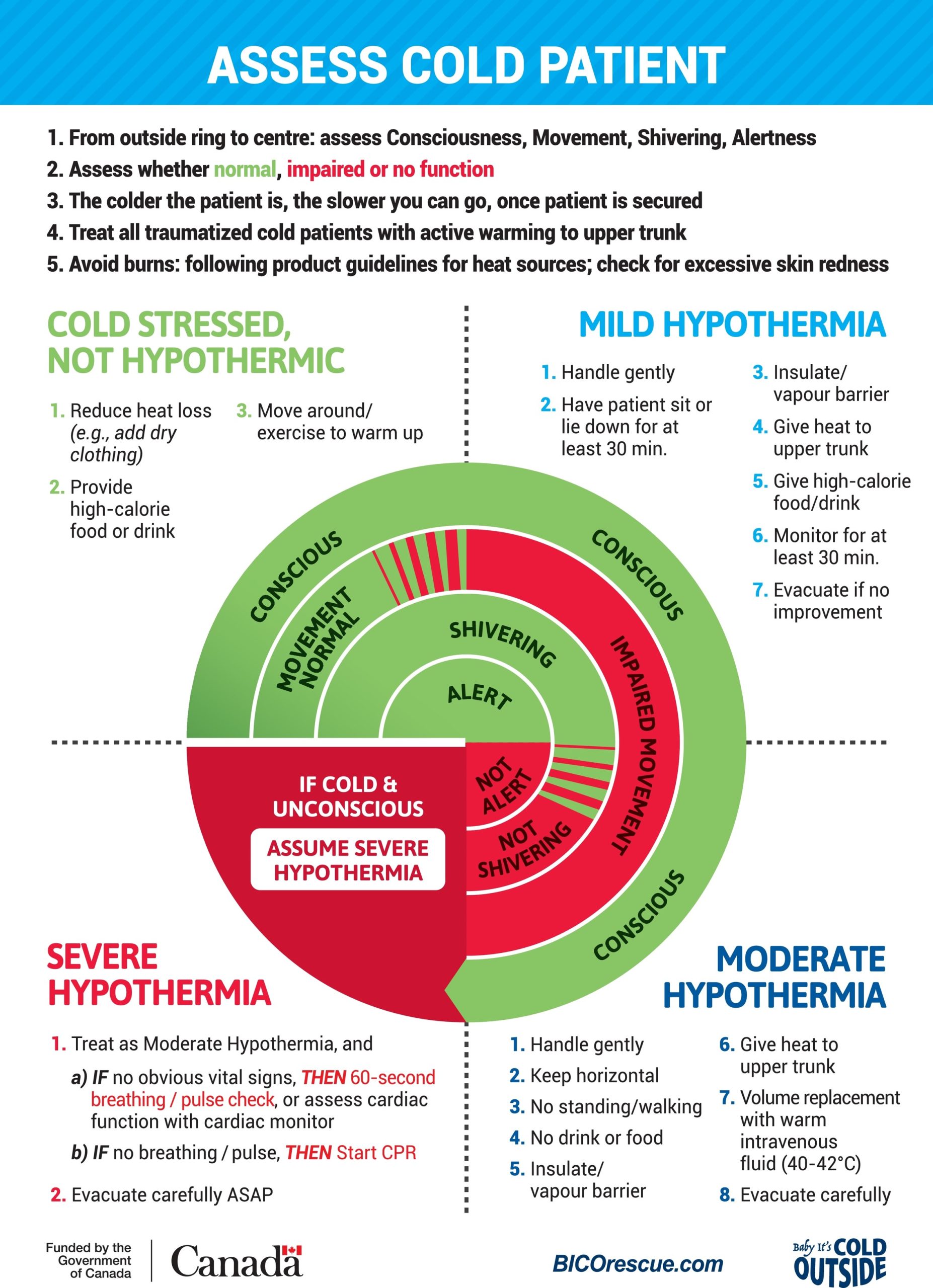

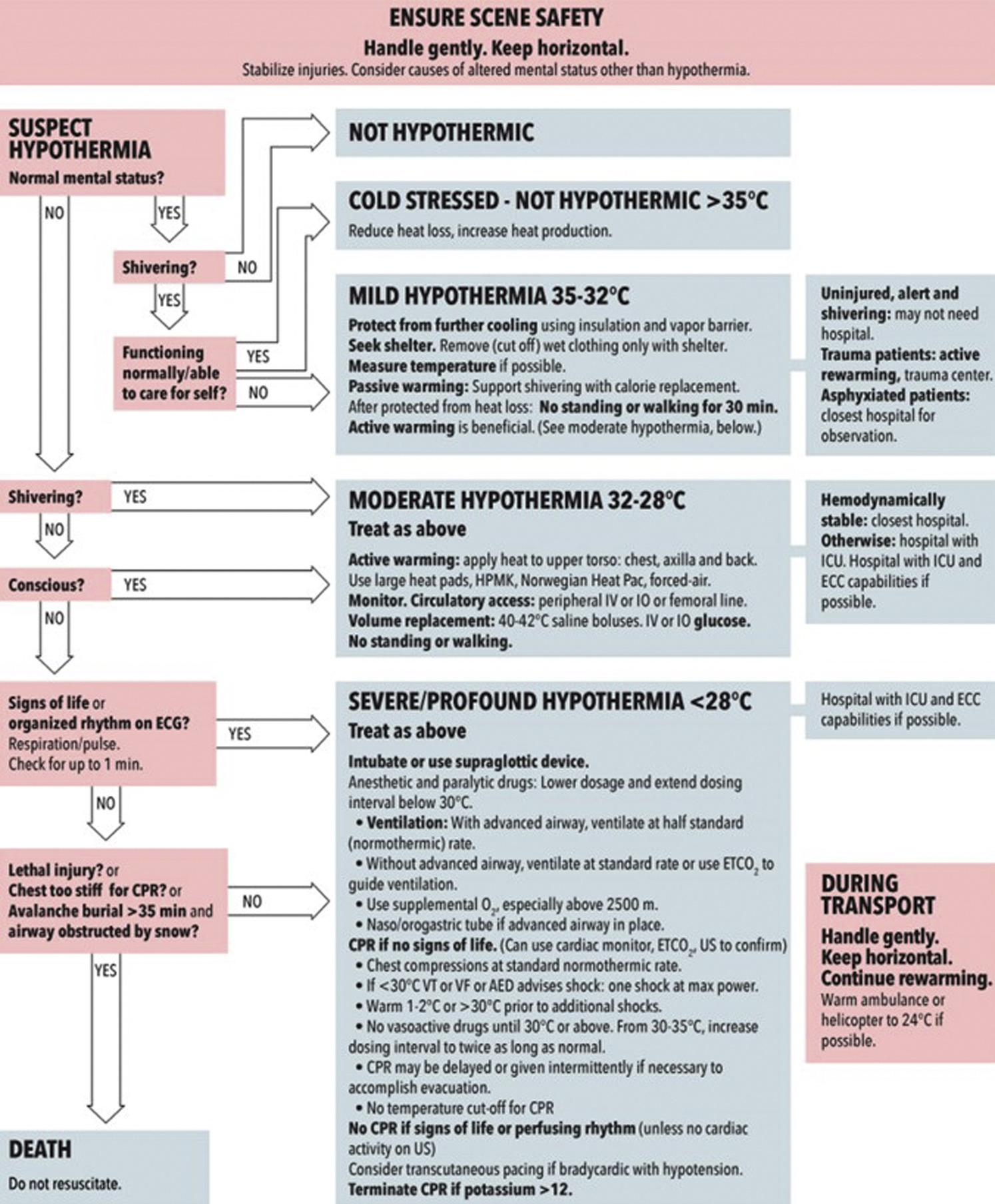

When the human body cools to a core body temperature <35°C (<95°F), a person with mild hypothermia feels cold and begins to shiver. Shivering, while an excellent physiological response to increase body temperature, is a warning sign. When people cannot seek shelter, or increase clothing insulation, or if energy stores are depleted so that continued shivering and exercise are unable to generate sufficient heat, hypothermia worsens. Symptoms of progressive hypothermia are confusion, clumsiness, and coma. See Figure 3.2.1 and Figure 3.2.2 for guidelines for field assessment and management of accidental hypothermia.

Travelers planning travel to cold climates should choose equipment and clothing designed to protect them from exposure (Table 3.2.2); innovative products may augment good clothing by providing electrical warmth, and many such garments may be recharged with a portable solar battery.

Cold water immersion is a risk for especially rapid cooling. If the person survives the involuntary gasp (cold shock) that may occur in the first minutes of contact with cold water, hypothermia may cause inability to swim within as little as 10 minutes. Use of a personal flotation device is critical to survival when travelers are at risk for immersion in cold water. Boating self-rescue classes are an important risk mitigation tool.

Figure 3.2.1

Gordon Giesbrecht

Figure 3.2.2

"Zafren, K., Giesbrecht, G. G., Danzl, D. F., Brugger, H., Sagalyn, E. B, Walpoth, B., . . . Grissom, C. K. (2014). Wilderness Medical Society practice guidelines for the out-of-hospital evaluation and treatment of accidental hypothermia: 2014 update. Wilderness & Environmental Medicine, 25(4 Suppl), S66–S85. ©2014 Wilderness Medical Society."

Table 3.2.2: Sample clothing layering for cold climate

| Layer | Material Examples | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Base | Silk, wool, polypropylene turtleneck, and leggings | Wicks moisture away from skin |

| Middle | Fleece, augment with down or insulating microfiber for extreme cold | Insulates, maintains warmth |

| Outer shell | Hooded, waterproof, breathable, windproof | Protects from wind and allows moisture out but not in |

Non-freezing cold injuries

Trench foot (or immersion foot) is a non-freezing cold-related injury of the neurovasculature caused by intense vasoconstriction coupled with pressure created by edema and clothing after prolonged immersion of the feet in water 15°C (<59°F) (Table 3.2.3). The first stage includes numbness and clumsiness during exposure that progresses on rewarming to stage 2 with mottling and color changes. Stage 3 involves hyperemia and pain with or without tissue loss. Stage 4 may leave the patient with intense sensitivity to repeated cold exposure and neuropathic pain. Treatment includes passive rewarming, drying, elevation, and analgesics.

Pernio (or chillblains) are purplish lesions that occur primarily on the skin of hands and earlobes on some susceptible individuals after exposure to cold wet conditions. Symptoms include pruritus and pain that are exacerbated by rapid rewarming. Prevention (keeping skin warm and dry) is key. Pharmacologic treatment with nifedipine shows promise; however, this use is considered off-label and warrants caution and clear instructions to the traveler because of the risk of hypotension with associated dizziness.

Frostbite

Frostbite injury begins with ice crystal formation in tissue. Vasoconstriction causes the mildest form of injury; deeper injury involves microvascular blood clotting and subcutaneous (muscle, bone) tissue necrosis in the most severe cases. With education and proper gear, most frostbite is preventable; the majority of cases occur in unprepared people unable to secure shelter or after accidents.

Superficial frostbite (1st and 2nd degree) may include reddening of the skin and edema with or without clear fluid-filled blister formation; superficial tissue loss is possible, but there is a favorable prognosis. Deep frostbite (3rd and 4th degree) involves vascular thrombosis, blood filled blisters, and deep tissue necrosis (Table 3.2.3).

Frostbitten skin may appear blanched and may feel numb. Efforts should be made to rewarm the skin quickly in water heated to 37°C–39°C (98.6°F–102.2°F). If no thermometer is available, test water with uninjured skin to ensure water is not scalding. Offer analgesics because rewarming may be intensely painful. Once tissue thaws, refreezing causes worsened injury, so it is preferable to delay rewarming until sustained thaw can be assured.

After rewarming, edema and clear or hemorrhagic (blood) blisters may form. Hemorrhagic bullae or cyanosis without blister formation imply deep tissue infarction, and appearance helps guide evacuation and advanced imaging and treatment decisions. Clean, dress, and pad injuries to protect against mechanical trauma, taking care to place dressings loosely in anticipation of further tissue swelling. Treatment with anti-inflammatory doses of ibuprofen (400 mg, twice daily) and aloe vera ointment or gel may be useful; in most cases, antibiotic prophylaxis is not indicated.

Technetium-99m (Tc-99m) scintigraphy and magnetic resonance imaging guide treatment and predict need for surgery and extent of tissue loss for patients with 3rd or 4th degree injury. Some advanced care settings employ protocols for the administration of thrombolytic agents or iloprost (which was used for years outside of the United States, but approved by the FDA in February 2024 for use in frostbite), but their use requires treatment within 48–72 hours of tissue thawing. Consultation with a clinician with experience treating frostbite optimizes outcomes in management of deep frostbite injury.

Table 3.2.3: Cold injuries

| Types of Cold Injury | Clinical Findings | Management | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Freezing: Occurs in wet settings 0°C–15°C (32°F–59°F) | |||

| Trench foot | Erythema or cyanosis or mottling | Dry passive rewarming, elevation, pain relief (ibuprofen if tolerated, narcotics if severe pain) | Avoid rapid active rewarming |

| Pernio | Erythrocyanotic papules, pruritus, pain | Dry, protect, prevent more cold/wet exposure, pain relief as above | |

| Freezing | |||

| Frostbite | Appearance after rewarming | Rapid water rewarming for all stages 37°C–39°C (98.6°F–102.2°F) with pain relief as above | Search for and treat any coexisting hypothermia first |

| First degree | Erythema, edema | Add ibuprofen 400 mg twice daily for anti-inflammatory effect if not already using for pain. | Increased vulnerability to future cold exposure |

| Second degree | Erythema, clear fluid-filled bullae | All above, may aspirate clear bullae | |

| Third degree | Cyanosis, hemorrhagic bullae, injury proximal to distal interphalangeal joint | All above, source definitive care for thrombolytics or iloprost within 48 hours, leave bullae intact | Technetium-99m (Tc-99m) scintigraphy or magnetic resonance imaging predicts tissue loss |

| Fourth degree | Cyanosis, no bullae, no cap refill | All above | As above |

- Dow, J., Giesbrecht, G. G., Danzl, D. F., Brugger, H., Sagalyn, E. B., Walpoth, B., . . . Grissom, C. K. (2019). Wilderness Medical Society clinical practice guidelines for the out-of-hospital evaluation and treatment of accidental hypothermia: 2019 update. Wilderness & Environmental Medicine, 30(4S), S47–S69. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.wem.2019.10.002

- Gauthier, J., Morris-Janzen, D., & Poole, A. (2023) Iloprost for the treatment of frostbite: A scoping review. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 82, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/22423982.2023.2189552

- Eifling KP, Gaudio FG, Dumke C, et al. Wilderness Medical Society Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Heat Illness: 2024 Update. Wilderness & Environmental Medicine. 2024;35(1_suppl):112S–127S. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/10806032241227924?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200pubmed

- Matsee, W., Charoensakulchai, S., & Khatib, A. N. (2023). Heat-related illnesses are an increasing threat for travellers to hot climate destinations. Journal of Travel Medicine, 30(4), 1–5. https://www.doi.org/10.1093/jtm/taad072

- McIntosh, S. E., Freer, L.., Grissom, C. K., Rodway, G. W., Giesbrecht, G. G., McDevitt, M., . . . Hackett, P. H. (2024). Wilderness Medical Society Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Frostbite: 2024 Update. Wilderness & Environmental Medicine, 35(2), 183–197. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/10806032231222359?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200pubmed

- Périard, J. D., Eijsvogels, T. M. H., & Daanen, H. A. M. (2021). Exercise under heat stress: Thermoregulation, hydration, performance implications, and mitigation strategies. Physiological Reviews, 101(4), 1873–1979. https://www.doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00038.2020

- Pryor, R. R., Roth, R. N., Suyama, J., & Hostler, D. (2015). Exertional heat illness: Emerging concepts and advances in prehospital care. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 30(3), 297–305. https://www.doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X15004628

- Sorensen, C., & Hess, J. (2022). Treatment and prevention of heat-related illness. The New England Journal of Medicine, 387(15), 1404–1413. https://www.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp2210623

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2024). FDA approves first medication to treat severe frostbite. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-medication-treat-severe-frostbite