Purpose

Introduction

International travelers who engage in outdoor activities are often exposed to more ultraviolet (UV) radiation (UVR) than usual, especially if their travels take them to sunnier locations, lower latitudes, or higher elevations. Even winter activities (e.g., snow skiing) can result in significant UVR exposure. Short bursts of high-intensity UVR (e.g., infrequent beach vacations), as well as frequent, prolonged, cumulative UVR exposure, can cause acute effects (e.g., sunburn and phototoxic medication reactions) and delayed effects from chronic exposure (e.g., sun damage, premature aging, cataracts, skin cancers).

Risk factors

Time of year, time of day, latitude, altitude, geographic location, and meteorological conditions all influence the amount of UVR that reaches any particular area of the earth's surface. Human behavior (attire, activities, time of day when outdoors, and sun-protective measures) determines how much UVR reaches a person's skin or eyes.

Most UVR reaches the earth's surface during summer months. Ultraviolet B (UVB), which is more carcinogenic than ultraviolet A (UVA), is most intense during mid-day (10 a.m. to 4 p.m.), at higher elevations, and as one gets closer to the equator. Features on the Earth's surface (such as snow, water, and sand) can reflect UVR, thereby increasing potential UVB exposure. Although UVA is less carcinogenic than UVB, UVA occurs at high intensity throughout daylight hours. UVA causes more acute photosensitivity reactions than UVB, and it contributes more to premature aging.

Ultraviolet index

The U.S. National Weather Service calculates and publishes a daily ultraviolet index (UVI) for most U.S. locations. The UVI is calculated using computer models that couple solar energy delivered at ground level with the ozone forecast. This value is further adjusted for elevation, atmospheric aerosol properties, and cloud conditions. The globally accepted UVI scale uses a 0–11+ scoring system. The UVI ranges from 0 (at night or under a smoke-filled sky) to 11+ (in the tropics, at high elevation, with no cloud cover). Higher UVIs indicate greater risks for skin- and eye-damaging UVR. Global data for many sites outside the United States are available on the World Health Organization (WHO) website, where one can download a smartphone application that gives the UVI for global locations.

Underlying medical conditions

Certain medical conditions increase a person's risk of experiencing the adverse effects of UV exposure. For example, people with autoimmune connective tissue diseases (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus) have heightened photosensitivity. Combinations of immunosuppressive drugs, such as those used by solid-organ transplant recipients, are at much greater risk for UVB-induced skin cancers. Counsel these patients on how to protect themselves, especially during hours of maximal exposure.

Photosensitizing medications

Many medications, including several prescribed specifically for travelers, can lead to photosensitivity reactions. Examples include:

- Antibiotics, including doxycycline (and other tetracyclines to a lesser degree), fluoroquinolones, sulfonamides

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), especially ibuprofen, ketoprofen, naproxen, piroxicam

- Many types of cancer therapies (e.g., chemotherapeutic agents, radiation therapy, some immunomodulators) can be sun sensitizers during treatment, and effects can linger even after completion of therapy.

- Other common medications (e.g., furosemide, methotrexate, sulfonylureas, thiazide diuretics, retinoids).

Consequences

Sunburn

Sunburn is a common and self-limited condition. It is also preventable. Both UVA and UVB can cause sunburns, which is why people should use broad-spectrum sunscreens that protect from both types of UVR. Clinical features of sunburn vary from mild pink to painful red skin with edema and blisters on exposed surfaces. Systemic symptoms can include headache, fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, or muscle aches.

Sunburn management consists of symptomatic pain relief. People rarely notice the developing sunburn while the burn is occurring. Discomfort begins several hours to a day later and can be exquisitely painful. First-line supportive care consists of cool baths or showers and applying wet compresses and bland topical emollients (e.g., petrolatum, zinc oxide). Refrigerating topical emollients before application can provide added relief. Aloe vera is commonly used as a sunburn remedy, but studies assessing its benefit are equivocal.

In general, intact blisters should not be ruptured intentionally. However, if the blisters are tense or painful, then one may drain them in a sterile manner. Gently clean the skin with soap and water or with alcohol-based hand sanitizer, then use a heat-sterilized needle to nick the edge of the blister in 1 or 2 places. Use sterile gauze (or a clean paper towel) to absorb the draining blister fluid. Leave the blister roof intact to serve as a sterile dressing; it is more protective than standard adhesive bandages. If a dressing is applied over the blister, it should be loose so that it does not abrade and remove the blister roof.

Topical corticosteroids (e.g., hydrocortisone 1% cream or ointment) or diclofenac gel can decrease pain and inflammation. People with a sunburn typically benefit from rest in a cool setting, extra fluids, and oral pain relievers (e.g., acetaminophen, ibuprofen, naproxen). Systemic steroids do not improve symptoms or hasten recovery.

Patients with extensive blisters might require hospitalization for fluid replacement (oral or intravenous) and pain control. Treat these patients the same way as patients with thermal burns: maintain clean skin with gentle cleansing, then cover the sunburned areas liberally with emollients. As described above, tense or painful blisters can be drained in a locally sterile manner, but a blister roof should remain intact to serve as a sterile dressing.

Sun damage and skin cancer

High-intensity or chronic exposure to UVR (particularly UVA) causes coarse and fine wrinkling of the skin; permanent loss of skin elasticity; blotchy hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation; fine telangiectasias; and xerosis. Many fair-skinned people develop solar lentigines (brown macules with irregular borders that look like large freckles). The best way to avoid these skin changes is to take simple steps to avoid sun overexposure and sunburn.

WHO characterizes UVR as a carcinogen that has the potential to induce skin cancers via DNA damage. Skin cancers are the most common malignancies in the United States, and basal and squamous cell carcinomas (BCCs and SCCs) are closely linked to UV exposure. The National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health predicts that in 2023, 3.6 million BCCs and 1.8 million SCCs will be diagnosed in the United States.

The diagnosis of any skin cancer should be made on biopsied tissue, not on clinical features alone. BCCs commonly appear on sun-exposed areas, typically manifesting as pearly, red papules surrounded by tiny blood vessels (telangiectasias). BCCs often bleed, ulcerate, expand laterally, or grow into nodules. BCCs rarely metastasize and are generally cured with routine excision or other local treatments.

SCCs commonly present as scaly or rough-surfaced papules or plaques on sun-exposed areas. Advanced or long-standing SCCs are 10 times more likely to metastasize than BCCs. Solid-organ transplant patients who are on immunosuppressive therapy and patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia have an increased risk for SCCs.

Melanoma is less common than BCC or SCC, but it is a potentially much more serious form of skin cancer, and its incidence is increasing among most populations. Risk factors for melanoma include fair skin, genetic susceptibility, and a history of blistering sunburns before the age of 18. Melanomas have a variety of clinical presentations, the most common of which is an irregularly bordered, darkly pigmented, flat spot or raised papule on the skin that changes its size, shape, or both over time (Box 3.1.1). When a skin lesion raises clinical suspicion for melanoma, the patient should be referred for prompt evaluation and possible biopsy.

Of the various types of skin cancer, melanoma has the greatest morbidity and mortality; the National Cancer Institute estimates that in 2023, there will be approximately 98,000 new cases of cutaneous melanoma in the United States, and approximately 8,000 people will die from this cancer. Early detection and treatment (simple excision with clear margins) lead to complete recovery in most cases. Depending on the tumor stage, patients might need additional surgery; evaluation for metastasis and other forms of occult spread; treatment with chemotherapeutic or biological agents; and regular monitoring.

Box 3.1.1

Other photosensitivity disorders

Increased exposure to sunlight, particularly UVA, can exacerbate existing skin conditions and can cause or unmask photosensitivity disorders, such as autoimmune connective tissue diseases (e.g., dermatomyositis or systemic lupus erythematosus), phototoxic medication reactions, polymorphous light eruption, porphyrias, and solar urticaria. A person experiencing prolonged or severe symptoms after sun exposure (e.g., arthralgias, fever, pruritus, swelling) should seek medical evaluation.

Photo-onycholysis

Photo-onycholysis is a separation or lifting of the nail plate from the nail bed in people taking an oral photosensitizing agent, usually a medication, in association with intense sun exposure. The most common setting is someone taking doxycycline for malaria prophylaxis.

Phytophotodermatitis

Phytophotodermatitis is a noninfectious condition that results from action of UVA radiation on photosensitizing compounds (furocoumarins) that naturally occur in several plant families, in particular the citrus family (Rutaceae). In the tropics, the most common source is the photosensitizing juice of certain types of limes, often called Persian, wild, or key limes. A common scenario arises when a traveler squeezes fresh lime juice onto a food or beverage and, within a day or 2, develops a painful blistering rash on skin where the lime juice dripped or spritzed. Similarly, many fragrant products, such as perfumes and essential oils, often contain citrus oils, such as bergamot, that can induce rashes after sun exposure.

In northern temperate regions, an increasingly common source is giant hogweed (Heracleum mentagazzium). This weedy, quick-growing plant is native to Southwest Asia but is now widely invasive across central and northern Europe, the northern half of the United States, and Canada. It grows vigorously, especially in open meadows, and often exceeds 8 ft in height.

The interaction of UV light and the furocoumarins causes an exaggerated sunburn-like response that creates painful blisters where the photosensitizing juice or sap is on the skin. As the blisters heal, they are replaced by distinctive linear or drop-like hyperpigmented brown patches that can persist on the skin for weeks or months.

Prevention

Travelers can take steps to avoid overexposure to UVR (Box 3.1.2). To encourage safe sun behaviors, clinicians can remind travelers that UVB radiation is maximal during midday, UV exposure still occurs in cooler weather and on overcast days, and UVR increases with travel to lower latitudes (closer to the equator) and higher elevations.

Box 3.1.2

Sun avoidance

If possible, travelers can decrease UV exposure by avoiding exposure to direct sunlight during peak hours, between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. Travelers can reduce UV exposure by seeking shade under (or alongside) trees, umbrellas, or other natural or manmade structures. People should bear in mind that UV rays can be reflected by a variety of surfaces, including snow, water, and sand. Studies show that concomitant use of shade and sunscreen will protect people from excessive UVR far more effectively than reliance on a single method.

Sunscreens

Sunscreens are topical preparations containing substances that reflect or absorb light in the UV wavelengths, thereby reducing the amount of UVR that reaches the skin. Two types of ingredients are used in sunscreens to protect the skin from excessive UVR. These ingredients, known as UV filtering agents, fall into two categories: chemical (sometimes referred to as organic) UV filters; and physical (sometimes referred to as mineral or inorganic) UV filters. Commercial sunscreen products can contain chemical or physical filters, or both, and often include more than 1 of each type. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulates UV filtering agents and commercial sunscreens. Regulatory agencies in other countries often permit the use of UV filters not approved in the United States. See Box 3.1.3 for recommendations on choosing a sunscreen approved for sale in the United States. Additional UV filtering agents are available in commercial sunscreens made in different countries. Box 3.1.4 provides additional information on sunscreens available outside the United States.

Box 3.1.3

Box 3.1.4

Choosing a sunscreen

In this section, we use the term "UV filter" to mean the specific agent or molecule that provides protection from UV radiation. We use "commercial sunscreen" to mean the branded product that one buys and applies to one's skin. People use many criteria when selecting a commercial sunscreen, but in practical terms, the best sunscreens are those that people will apply properly and regularly.

UV filters are considered either chemical filters or physical filters. Most commercial sunscreens contain 2 or more UV filters. These can be chemical or physical or a mix of both types of UV filters. Chemical UV filters penetrate the upper layers of the epidermis, where they protect by "capturing" (or absorbing) UV light. Physical UV filters remain on the epidermal surface to reflect (or scatter and bounce back) UVR. See Box 3.1.3 for additional details on choosing sunscreens available in the United States.

Sun protection factor

A product's sun protection factor (SPF) is a ratio of the amount of UVB radiation required to cause a sunburn on skin protected by a topical sunscreen product vs the amount of UVB radiation required to cause a sunburn on unprotected skin. SPF measures protection from UVB only, not UVA. As most people know: the higher the SPF, the greater the degree of protection from UVB and from sunburn.

The FDA uses a strict protocol to determine a product's SPF. In theory, an SPF of 30 means that only 1/30th of the UVB reaches the skin—or that a person can remain in the sun 30 times as long—when the sunscreen is applied. To effectively attain the desired SPF, however, a person must start by applying an adequate amount of sunscreen, avoid rinsing or rubbing (this causes uneven coating of skin and product accumulating in wrinkles, folds, and other skin creases) or sweating it off, and reapply it every 2 hours. From a mathematical perspective, sunscreens rated as SPF 30 block 97% of UVB, those rated as SPF 50 block 98%, and those rated as SPF 100 block 99%. The FDA discourages claims of SPF >50 on a product's label because the incremental increase of UV protection is clinically irrelevant. The terminology that the FDA uses to describe sunscreens is outlined in Box 3.1.5.

Box 3.1.5

Chemical (organic) UV filters

Sunscreens with chemical UV filters are absorbed into the outer layers of the skin and work like a sponge to absorb UV energy. The chemical UV filters currently approved for use in the United States vs Europe, Japan, and Australia are listed in the table in Box 3.1.4. Products containing chemical UV filters can be easier to apply and are less likely to leave a white residue than physical UV filters. People with naturally dark skin may avoid certain sunscreens because they leave a pale or ashy appearance; however, people with darker skin tones also need protection against the short- and long-term effects of UVR described above.

Do not misinterpret the term "organic" when applied to sunscreens. Chemical UV filters are also called "organic filters" because they are carbon-based organic molecules, not because they have any of the purportedly natural benefits that are associated with the colloquial use of this word. In fact, organic sunscreens pose more potential risks to individuals and the environment than inorganic (or physical) sunscreens, which are discussed in the next section.

Box 3.1.6 provides information on some possible health risks associated with using chemical UV filters.

Box 3.1.6

Physical (mineral or inorganic) UV filters

Physical UV filters, often called mineral or inorganic filters, reflect both UVA and UVB from the skin's surface. Worldwide, only 2 products are used as physical filters: zinc oxide and titanium dioxide. These metallic oxides are pulverized into microparticle or nanoparticle size and then are mixed with a vehicle or emollient that permits them to be applied smoothly to the skin. Sunscreens might contain none, 1, or both physical agents. Currently, available commercial sunscreen products are made with a combination of both physical and chemical UV filters.

Physical sunscreens pose very little risk of causing allergic or irritant contact dermatitis (Box 3.1.6). They can, however, leave a residual white film or hue on the skin. Nevertheless, current products are cosmetically more acceptable than the thick, opaque pastes commonly used in the late 20th century.

In recent years, tinted sunscreens have become available and they are cosmetically more acceptable to people with darker skin complexions. These products usually contain micro-pulverized iron oxide or pigmentary titanium dioxide. Iron oxide has additional benefits in that it filters (or blocks) certain wavelengths of visible light that contribute to photoaging, melasma, and other conditions marked by blotchy hyperpigmentation.

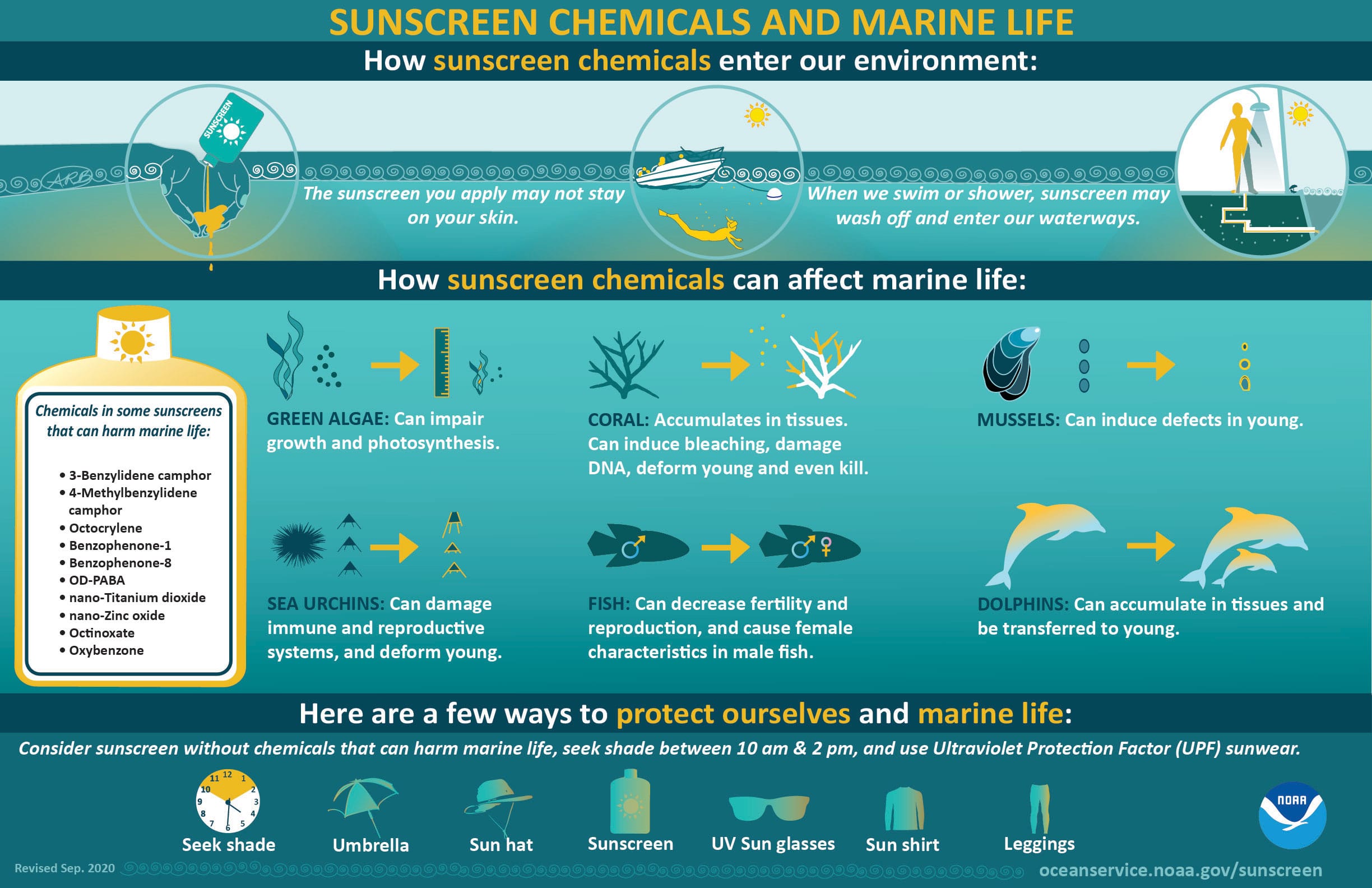

Physical filters do not have the adverse environmental effects associated with many chemical UV filters (Box 3.1.7 and Figure 3.1.1). Accordingly, many people decide to buy only those commercial sunscreens that contain physical UV filters alone (and entirely omit chemical filters). Indeed, some tropical beach locations have adopted environmental protection policies that prohibit sunscreens with chemical UV filters. Locations with such policies include Aruba, Bonaire, parts of Mexico, Palau, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. In 2018, Hawaii passed a law banning sunscreens containing octinoxate and oxybenzone due to their potential toxic effects on coral and other marine life.

Box 3.1.7

Figure 3.1.1

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

Sunscreens for children

Because no UV filter has been approved for children <6 months of age, infants should have very limited exposure to direct sunlight, especially at midday. Parents or guardians can protect infants from direct sun exposure, opting for shade and dressing children in lightweight, long-sleeved shirts, long pants, wide-brimmed hats, and sunglasses. At this age, infants can be protected with covered strollers or perambulators, umbrellas or parasols, and portable shade shelters, rather than by applying sunscreen.

Children >6 months of age can be protected by applying commercial sunscreens that contain only physical (mineral) UV filters (titanium dioxide, zinc oxide, or both), rather than chemical UV filters. Physical UV filters are less likely to irritate young children's sensitive skin. Teens may prefer an oil-free sunscreen for the face to help avoid acne flares possibly associated with thicker, oily preparations. Moreover, teens can be reminded that sun-induced erythema usually makes pimples more noticeable. Adults can safely use commercial sunscreens marketed for children.

Applying sunscreen

Sunscreen guidelines recommend using sunscreens that are labeled as SPF ≥30 and that provide broad-spectrum protection from both UVA and UVB (Box 3.1.4; Box 3.1.5). The average adult needs 1 fluid ounce (equivalent to 2 U.S. tablespoons or 1 shot glass full) with each application. Spread the sunscreen gently and evenly on all exposed skin. It is not necessary to rub it to the point of vanishing. Vigorous rubbing causes the sunscreen to accumulate in wrinkles, creases, and other subtle irregularities of the skin's surface. The converse is true, too: vigorous rubbing effectively removes sunscreen from smooth and subtly raised areas of skin. For optimal effectiveness, sunscreens that contain chemical UV filters should be applied ≥15 minutes before going outside. This allows the chemical UV filters to enter the outer skin layers, where they are most effective. Sunscreens that have only physical UV filters do not require a 15-minute delay. Sunscreen should be reapplied to all exposed areas every 2–4 hours.

Sunscreens come in many forms, including lotions, creams, oils, sticks, roll-ons, and sprays. In general, lotion- or cream-based sunscreens can be applied in the most reliable manner. Stick or roll-on sunscreens are easy to apply, but people often apply these unevenly, leading to skipped areas that sunburn easily. People who use stick or roll-on sunscreens should gently spread the product after application.

Spray sunscreens

Spray sunscreens seem easy to apply, and many young kids prefer sprays to having a parent apply sunscreen all over their bodies. However, spray sunscreens are not highly recommended. People generally apply them unevenly, especially under breezy conditions. Consumer Reports (2020) recommends that one should hold the spray nozzle 1 inch from the skin; spray until the skin glistens uniformly; then gently spread the product to coat the skin evenly, even if the product claims to be "no rub." Some environmental health organizations discourage the use of spray sunscreens because the contents are likely to get into the environment as much as they get onto a person's skin.

Avoid spraying the sunscreen on or near the face, because the particulate components can injure the eyes or damage lung tissue if inhaled. To use on the face, people should spray their palms and then apply the sunscreen gently and thoroughly. Similarly, one should avoid using spray products with small children due to the risk of inhaling the aerosolized particles or getting the product in children's eyes. Instead, adults should spray the product on their own hands and then apply it to the child's skin.

Combination sunscreen and insect repellent

Some commercial products combine sunscreen and insect repellent, giving an allure of convenience. However, there are no reliable data on the shelf-life and retention of SPF efficacy for such products. Furthermore, combination products like these increase the potential for allergic or irritant reactions. Also, sunscreens need to be reapplied much more frequently than insect repellents. Sunscreen should be applied first, allowing it to reach optimal effectiveness. Next, insect repellent may be applied ≥15 minutes later. Sunscreens may be reapplied (over the insect repellent) every 2 hours during a day of long-term sun exposure.

Sunscreens and insect repellents are both effective and safe when used separately but, if combined, problems can arise. Certain sunscreen formulations decrease in their ability to screen out UV radiation when used with N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide (DEET), the most effective and most commonly used repellent. In some studies, the SPF was reduced by 30% in the combination products. In addition, sunscreens enhance absorption of DEET into the skin, potentially increasing toxicity—especially in children.

Protective clothing

Sun-protective garments (e.g., pants, long-sleeved shirts, hats) protect against UVR, but efficacy depends on the fabric. Thicker fabrics with tighter or denser weaves (e.g., denim) offer a higher ultraviolet protection factor (UPF). Like SPF, the UPF of a fabric or material represents the fraction of UVR that penetrates the material. UPF 50, for example, means only 1/50th of the ambient UVR gets through the fabric; 98% of UVR is blocked. A UPF rating of 15–24 is considered good, 25–39 is very good, and ≥40 is excellent. Many manufacturers of outdoor clothing and activewear now use densely woven, lightweight, quick-drying, synthetic UPF fabrics to make extremely comfortable shirts, pants, and hats.

Many companies use UPF fabric to make swim-shirts, also called rash guards. Swim-shirts are available with short or long sleeves; some have built-in hoods. Because UPF 50 fabric blocks 98% of UVR, a person does not need to apply sunscreen to surfaces covered by the shirts. This may appeal to parents of young children who dislike having sunscreen applied. Surfers, lap swimmers, and open-water swimmers might prefer smaller, tighter sizes for a streamlined (hydrodynamic) feel in the water.

Hats

The ideal hat has a circumferential brim ≥3 inches (approximately 75 mm) wide that shades the face, neck, and ears. People should not rely on standard baseball caps for sun protection because these do not protect the ears or neck. Instead, people should consider buying sun-specific caps with ear and neck flaps, many of which are made of UPF fabrics. These can be quite effective, especially for children.

Sunglasses

Protecting one's eyes is a necessary but often overlooked part of UVR protection. Anytime one is outside during daylight, eyes are exposed to various amounts of UVR, which can have short- and long-term effects that may damage the eyes and affect vision. UVR can penetrate clouds and haze, so people should protect their eyes regardless of atmospheric conditions. Wearing sunglasses is the paramount step in protecting one's eyes from UVR.

UVA can harm central vision by damaging the macula (the central focus area of the retina) in the back of the eye. UVB can damage the cornea and lens in the front of the eye. Intense UVB exposure, even over several hours, can cause corneal sunburn, also called photokeratitis or snow blindness. It is an exquisitely painful condition. The sensitivity to light (photophobia) can force a person to keep their eyes closed for several hours or more. Snow blindness can occur when UVR reflected off snow nearly doubles the amount of UVB that reaches the eyes. Other symptoms include copious tearing (watery eyes), injected sclera (noninfectious pink eye), or a gritty foreign-body sensation of the eye. These symptoms are usually temporary and rarely cause permanent damage to the eyes—but corneal burns are extremely disabling during the painful hours that one must keep the eyes closed. Long-term UVR exposure can lead to cataract formation, age-related macular degeneration, benign conjunctival growths of scar tissue (called pterygium and pinguecula), and cancers of the eyelids and conjunctiva.

The proper selection of sunglass lenses is an important step for protecting the eyes. Not all sunglasses provide UV protection for the eyes. Wrap-around sunglasses or those with sun-blocking side shields provide the best UV protection. People should choose close-fitting frames that contour to the shape of the face to prevent exposure to direct and reflected UVR from all sides and angles. The American National Standards Institute (ANSI) has a standard that applies to sunglasses (ANSI Z80.3—Sunglasses Requirements); synopsis of this standard.

People should choose sunglasses with polarized lenses that are rated UV 400 and meet the ANSI Z80.3 standard; these block nearly 100% of damaging UVR. Lenses should have a uniform tint throughout. The tint color (e.g., amber, gray, green, black) does not affect sun protection efficacy, but gray tints provide the best color fidelity. Polarized or mirrored lenses are not more effective at protecting against UVR, but they do reduce the amount of reflected light entering the eye. Inexpensive, non-branded sunglasses rated UV 400 are just as effective as expensive, designer-label sunglasses. Lenses can be glass or plastic. Modern sunglasses may have UVR protection and polarization incorporated into the lenses themselves. Sunglasses that meet or exceed the ANSI standard should be labeled as such. Parents or guardians should provide appropriate eye protection for children. Some contact lenses offer a modicum of UV protection, but people should also wear sunglasses with contact lenses.

The American Academy of Ophthalmology and the American Optometry Association provide recommendations and information on gradient, transitional, and prescription sunglasses at these websites: Tips for Choosing the Best Sunglasses; Recommended Types of Sunglasses; and Ultraviolet (UV) Protection.

Beach umbrellas and sun-shade shelters

Several types of shade shelters are available: umbrellas, canopies, and tents. Many shelters marketed for sun-shade combine several features. People should choose a shelter made with a fire-resistant UPF 50 fabric, usually nylon or polyester, that has a durable yet lightweight frame. Additional features to consider are the size needed to accommodate the number of people who will use the shelter; weight and the ability to collapse and easily transport the shelter; water-resistant fabric for rain squalls; open or mesh sides that allow adequate air circulation; ability to securely anchor the shelter to the ground with stakes, fillable sandbags, or a combination; and easy assembly, ideally by 1 person. Standard camping tents generally are unsuitable for shade shelters unless they are rated as such.

Travelers should select beach umbrellas with ample diameter and directional tilt, so the protective field can be adjusted as the sun rises and crosses the sky. Tall umbrellas with a small surface area lose their protective benefits when the sun is at a low angle. Wind gusts can uproot and launch umbrellas, posing a safety hazard. Therefore, people should select an umbrella with parts that can be attached securely to each other and placed firmly in the ground. Screw-type bases can anchor an umbrella in the sand but are usually sold separately. Travelers should be aware that some public beaches limit the size of shade shelters.

Sunless tanning

Topical sunless tanning products are a safer way in which people can gain a tanned look. Although these products make the skin appear darker, they do not provide photoprotection, and travelers should still use sunscreen when exposed to UVR. Sunless tanning products can produce streaking when people sweat or go swimming and can generate an unnatural orange hue on areas of the skin where applied.

Many people believe that getting a pre-vacation tan by using tanning beds will help protect them from vacation sunburns. However, tanning bed lights rely on UVA, which is associated with premature aging. Tanning by this method is roughly equivalent to using an SPF 4 sunscreen, which will not prevent sunburns or other forms of solar damage.

Additional sources of information

Consumer Reports and the Environmental Working Group review and rate sunscreen products and their components annually. In general, Consumer Reports ratings emphasize human safety, ease of use, truth in advertising, cost, and performance, while the Environmental Working Group emphasizes environmental safety. Both identify sunscreens by brand name.

- Calvo, T. (2023). Sunscreen buying guide. Consumerreports.org. https://www.consumerreports.org/health/sunscreens/buying-guide/

- Fivenson, D., Sabzevari, N., Qiblawi, S., Blitz, J., Norton, B. B., & Norton, S. A. (2020). Sunscreens: UV filters to protect us: Part 2: Increasing awareness of UV filters and their potential toxicities to us and our environment. International Journal of Women's Dermatology, 7(1), 45–69. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.08.008

- Mitchelmore, C. L., Burns, E. E., Conway, A., Heyes, A., & Davies, I. A. (2021). A critical review of organic ultraviolet filter exposure, hazard, and risk to corals. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 40(4), 967–988. https://www.doi.org/10.1002/etc.4948

- Monteiro, A. F., Rato, M., & Martins, C. (2016). Drug-induced photosensitivity: Photoallergic and phototoxic reactions. Clinics in Dermatology, 34(5), 571–581. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.05.006

- Religi, A., Backes, C., Moccozet, L., Vuilleumier, L., Vernez, D., & Bulliard, J. L. (2018). Body anatomical UV protection predicted by shade structures: A modeling study. Photochemistry and Photobiology, 94(6), 1289–1296. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/php.12949

- Sabzevari, N., Qiblawi, S., Norton, S. A., & Fivenson, D. (2021). Sunscreens: UV filters to protect us: Part 1: Changing regulations and choices for optimal sun protection. International Journal of Women's Dermatology, 7(1), 28–44. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.05.017

- Suh, S., Pham, C., Smith, J., & Mesinkovska, N. A. (2020). The banned sunscreen ingredients and their impact on human health: A systematic review. International Journal of Dermatology, 59(9), 1033–1042. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/ijd.14824

- US Preventive Services Task Force, Grossman, D. C., Curry, S. J., Owens, D. K., Barry, M. J., Caughey, A. B., . . . Tseng, C. W. (2018). Behavioral counseling to prevent skin cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA, 319(11), 1134–1142. https://www.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.1623

- Wisconsin Department of Health Services. Medications and other agents that increase sensitivity to light. DHS.Wisconsin.gov. https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/radiation/medications.htm

- Young, A. R., Claveau, J., & Rossi, A. B. (2017). Ultraviolet radiation and the skin: Photobiology and sunscreen photoprotection. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 76(3 S1), S100–S109. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2016.09.038