Purpose

Introduction

Infectious agent

Leptospira spp.

Endemicity

Worldwide, higher incidence in tropical areas and areas of poor sanitation

Traveler categories at greatest risk for exposure and infection

Adventure tourists, outdoor athletes, and others exposed to fresh water or mud

Humanitarian aid workers, particularly at sites of hurricanes or floods

Military personnel

Prevention methods

Avoid contact with animal urine and water or soil contaminated with animal urine

Wear waterproof protective clothing and shoes or boots near floodwater or other water or soil that may be contaminated with animal urine

Cover cuts or scratches with waterproof bandages or other coverings that seal out water

Consider chemoprophylaxis for individuals with short-term exposures in areas of known high risk

Diagnostic support

A clinical laboratory certified in high complexity testing; state health department; or contact CDC’s Bacterial Special Pathogens Branch (bspb@cdc.gov) for diagnostic testing

Infectious agent

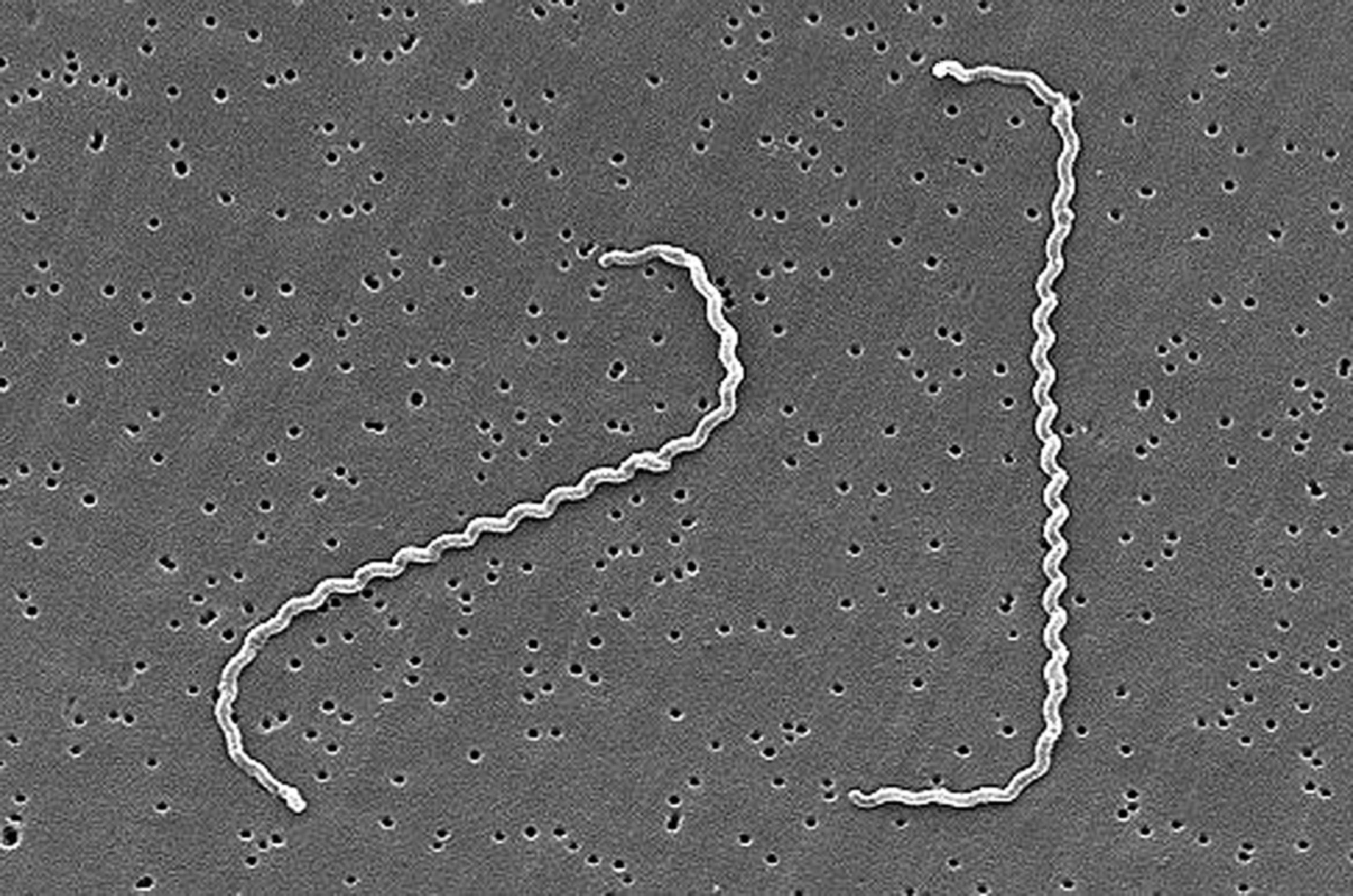

Leptospira spp., the causative agents of leptospirosis, are obligate aerobic, gram-negative spirochete bacteria.

Transmission

Leptospira are transmitted through abrasions or cuts in the skin, or through the conjunctiva and mucous membranes. Skin maceration resulting from prolonged water exposure is another suspected risk factor for infection. Humans can be infected by direct contact with urine or reproductive fluids from infected animals, through contact with urine-contaminated freshwater sources or wet soil, or by consuming contaminated food or water. Infection rarely occurs through animal bites or human-to-human contact. Rodents are an important reservoir for Leptospira, but most mammals, including dogs, horses, cattle, and swine, and many wildlife and marine animals, can be infected and shed the bacteria in their urine.

Epidemiology

Leptospirosis has a worldwide distribution; however, incidence is greater in tropical climates. Regions with the highest estimated morbidity and mortality include parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, parts of Latin America, the Caribbean, South and Southeast Asia, and Oceania. Specific country incidence rates are usually not available because leptospirosis is not reportable in many countries and there are gaps in diagnostic access. Travelers to endemic areas are at increased risk when participating in recreational freshwater activities (e.g., white water rafting, kayaking, boating, camping, hiking, swimming, fishing), particularly after heavy rainfall or flooding. Prolonged exposure to contaminated water and activities that involve head immersion or swallowing water increase the risk for infection.

Participating in activities involving mud (e.g., adventure races) also increases a traveler's risk for infection, as does working directly with animals in endemic areas, especially when exposed to their body fluids, and visiting or residing in areas with rodent infestation. Leptospirosis occurs most commonly in adult males. The estimated worldwide annual incidence is >1 million cases, including approximately 59,000 deaths.

Outbreaks can occur after heavy rainfall or flooding in endemic areas, especially in urban areas of low- and middle-income countries, where housing conditions and sanitation are poor and rodent infestation is common. Outbreaks of leptospirosis have occurred after flooding in popular U.S. travel destinations, including Florida, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Most U.S. cases are reported outside the continental United States in the domestic travel destinations of Hawaii and Puerto Rico.

Clinical presentation

The incubation period for leptospirosis is 2–30 days, but illness usually occurs 5–14 days after exposure. Most infections are thought to be asymptomatic, but clinical illness can present as a self-limiting acute febrile illness, estimated to occur in approximately 90% of clinical infections, or as a severe, potentially fatal illness with multiorgan dysfunction in 5–10% of patients. In patients who progress to severe disease, the illness can be biphasic, with a temporary decrease in fever between phases.

The acute, septicemic phase lasts approximately 7 days and presents as an acute febrile illness with symptoms including: headache, which can be severe and include photophobia and retro-orbital pain; chills; myalgia, characteristically involving the calves and lower back; conjunctival suffusion, characteristic of leptospirosis but not occurring in all cases; nausea; vomiting; diarrhea; abdominal pain; cough; and rarely, a skin rash.

The second or immune phase is characterized by antibody production and the presence of leptospires in the urine. In patients who progress to severe disease, clinical findings can include cardiac arrhythmia, hemodynamic collapse, hemorrhage, jaundice, liver failure, aseptic meningitis, pulmonary insufficiency, and renal failure. The classically described syndrome, Weil's Syndrome, consists of renal and liver failure.

Among patients with severe disease, the case-fatality ratio is 5–15%. Pulmonary hemorrhage is a rare but severe complication of leptospirosis that can have a case-fatality ratio >50%. Poor prognostic indicators include older age, development of altered mental status, respiratory insufficiency, or oliguria (decreased urine output).

Diagnosis

Submit a combination of samples for leptospirosis testing, including blood, serum, and urine samples; whenever possible, obtain paired acute and convalescent serum samples. During early disease, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of whole blood (collected in the first week of illness) and urine (collected after the first week of illness) can be helpful. PCR analysis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) also can be helpful in diagnosing patients with signs of meningitis.

Diagnosis of leptospirosis is often based on serology; microscopic agglutination test (MAT) is the reference standard and can only be performed at certain reference laboratories. Various serologic screening tests are available at commercial laboratories, including enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and ImmunoDOT/DotBlot rapid diagnostic tests. The use of IgM-specific serologic screening tests is recommended, and positive screening tests should be confirmed with MAT. The sensitivity of serology increases in the second week of illness, although antibodies can sometimes be detected by day 3 or 4 following symptom onset.

Detection of the organism in acute whole blood using PCR can provide a timelier diagnosis during the early, septicemic phase, and PCR also can be performed on CSF or convalescent urine. A positive PCR result is confirmatory for infection. Culture is insensitive, is slow, and requires special media; it is therefore not recommended as the sole diagnostic method.

The Zoonoses and Select Agent Laboratory at the CDC performs MAT and PCR for diagnosis of leptospirosis. See clinician information on diagnostic testing at CDC and sample submission instructions. Clinicians can receive expert consultation on a suspected leptospirosis case by contacting CDC's Bacterial Special Pathogens Branch, or by calling the CDC Emergency Operations Center (770-488-7100). Leptospirosis is a nationally notifiable disease; see the Council for State and Territorial Epidemiologists' case definition.

Treatment

If leptospirosis is suspected, initiate antimicrobial therapy as soon as possible, without waiting for diagnostic test results. Early treatment can be effective in decreasing the severity and duration of infection. For patients with mild symptoms, doxycycline is a drug of choice, unless contraindicated; alternative options include ampicillin, amoxicillin, or azithromycin. Intravenous penicillin is the drug of choice for patients with severe leptospirosis; ceftriaxone and cefotaxime are alternative antimicrobial agents. As with other spirochetal diseases, antibiotic treatment of patients with leptospirosis might cause a Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction, an acute febrile reaction frequently accompanied by headache, myalgia, and fever that can occur within the first 24 hours after the initiation of antibiotic treatment. The reaction is rarely fatal. Patients with severe leptospirosis might require hospitalization and supportive therapy, including intravenous hydration and electrolyte supplementation, dialysis in cases of oliguric renal failure, and mechanical ventilation in cases of respiratory failure.

Prevention

The best way to prevent infection is to avoid exposure. Advise travelers to avoid exposure to potentially contaminated bodies of freshwater, flood waters, potentially infected animals or their body fluids, and areas with rodent infestation. Educate travelers who might be at increased risk for infection to consider taking additional preventive measures (e.g., wearing protective clothing, especially footwear), instructing them to cover cuts and abrasions with occlusive dressings, and counseling them on boiling or chemically treating potentially contaminated drinking water. Limited studies have shown that chemoprophylaxis with doxycycline (200 mg orally, weekly), begun 1–2 days before and continuing through the period of exposure, might be effective in preventing clinical disease in adults and could be considered for people at high risk and with short-term exposures. No human vaccine is available in the United States.

- Brett-Major, D. M., & Coldren, R. (2012). Antibiotics for leptospirosis. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (2), CD008264. https://www.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008264.pub2

- Costa, F., Hagan, J. E., Calcagno, J., Kane, M., Torgerson, P., Martinez-Silveira, M. S., Stein, C., Abela-Ridder, B., & Ko, A. I. (2015). Global morbidity and mortality of leptospirosis: A systematic review. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 9(9), e0003898. https://www.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0003898

- Haake, D. A., & Galloway, R. L. (2021). Leptospiral Infections in humans. Clinical Microbiology Newsletter, 43(20), 173–180. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.clinmicnews.2021.09.002

- Picardeau, M., Bertherat, E., Jancloes, M., Skouloudis, A. N., Durski, K., & Hartskeerl, R. A. (2014). Rapid tests for diagnosis of leptospirosis: current tools and emerging technologies. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease, 78(1), 1–8. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.09.012