Purpose

Introduction

International travel has risen steadily since the advent of commercial air travel and peaked at approximately 1.5 billion arrivals in 2019 prior to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Following arrival at their destination, travelers often experience jet lag, a sleep disorder caused by rapid travel across time zones, resulting in a temporary desynchronization between the internal biological clock and the local time. Jet lag disorder is not just a general feeling of low energy. It can manifest as sleep disturbances, cognitive impairment, daytime sleepiness, general malaise, gastrointestinal disturbances, and/or other symptoms (Table 7.4.1). There are limited data on the prevalence of jet lag disorder, but one recent survey reported that 68% of international business travelers experienced negative symptoms on a regular basis. While most travelers can cope with occasional jet lag, it is important to consider the factors that may make it more severe and therefore merit special consideration for both the traveler and the travel clinic. Risk factors for the development of jet lag disorder include the number of time zones traveled, exposure to appropriate time cues at the destination, individual genetic differences, use of medications, and other individual- and route-specific risk factors.

Table 7.4.1: Diagnostic criteria for jet lag disorder

A.

Insomnia or excessive daytime sleepiness, accompanied by a reduction of total sleep time, associated with trans-meridian travel across at least 2 time zones.

B.

Impairment of daytime function, general malaise, or somatic symptoms (e.g., gastrointestinal disturbance) within 1–2 days after travel.

C.

The sleep disturbance is not better explained by another current sleep disorder, medical or neurological disorder, mental disorder, medication use, or substance use disorder.

Notes

American Academy of Sleep Medicine. (2014). The International Classification of Sleep Disorders (3rd ed.) (ICSD-3). Diagnostic criteria for jet lag disorder, a circadian rhythm sleep disorder subtype. Criteria A–C must be met.

Prevention of jet lag symptoms is of great interest to the traveler and the travel clinic, and it is important to differentiate the effects for infrequent travelers and frequent travelers. Pre- and post-travel planning to minimize jet lag is most critical for frequent travelers owing to the significant and additive negative health effects of chronic insufficient sleep and circadian disruption.

It is important to understand the terminology related to circadian physiology. "Advancing" the circadian rhythm means that the internal biological body clock is being moved earlier in time to encourage the individual to want to fall asleep earlier and wake up earlier. "Delaying" the circadian rhythm means that the internal biological body clock is being moved later in time to encourage the individual to want to fall asleep later and wake up later. When traveling east, the "clock on the wall" shifts later, which makes the traveler relatively "delayed." The traveler must advance the biological clock to match the clock on the wall. When traveling west, the clock on the wall shifts earlier and the traveler must delay the biological clock to match the clock on the wall.

For most people, it is easier to delay than advance the circadian rhythm since the average period of the intrinsic circadian rhythm is slightly longer than 24 hours. Another way of saying this is that people naturally want to go to bed a bit later each night even in the absence of time zone travel. As such, westward travel is easier to adapt to than eastward travel, with an average rate of adaptation of 1.5 hrs/day for westward travel and 1 hr/day for eastward travel.

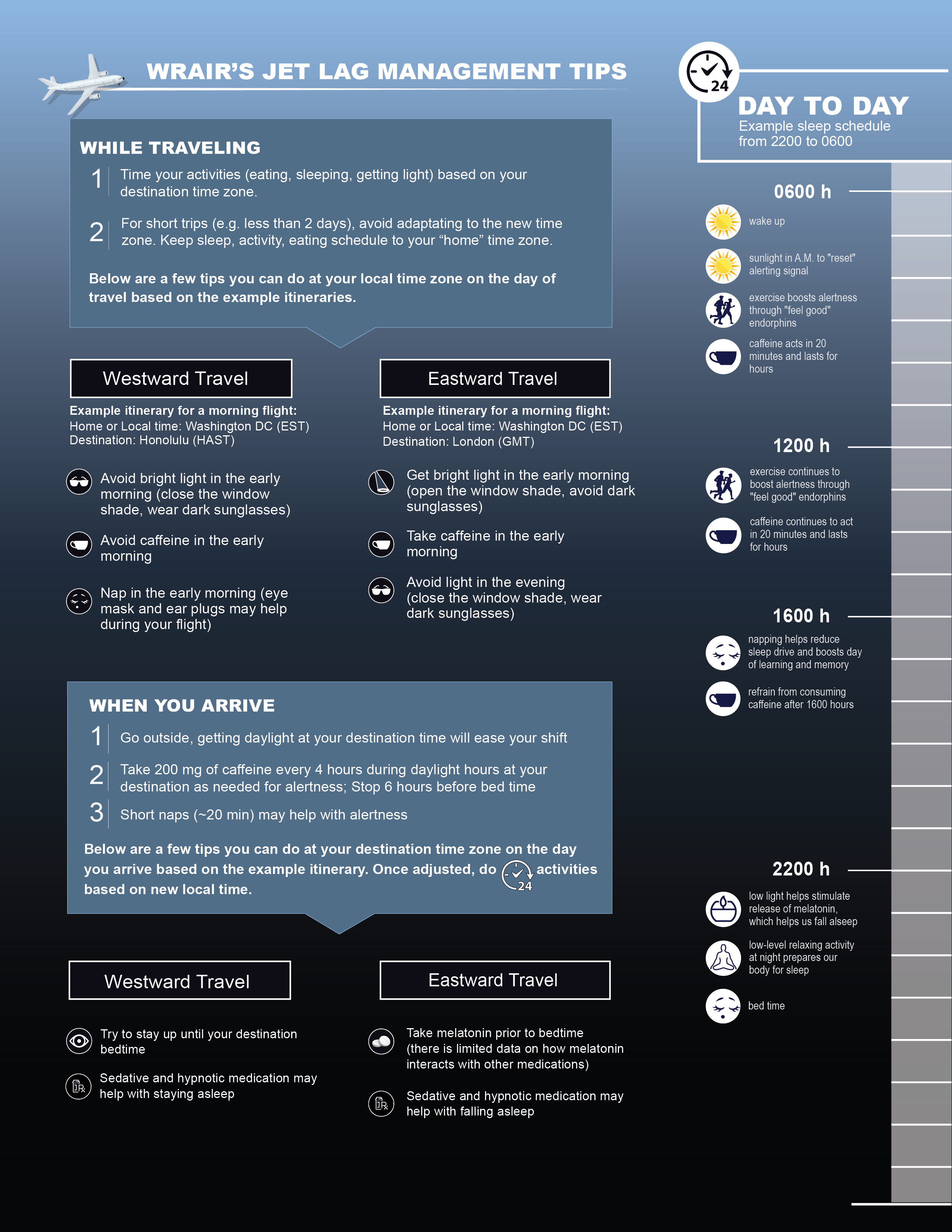

In the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) clinical practice guidelines for circadian rhythm sleep disorders, standard treatment for jet lag disorder in frequent travelers includes timed melatonin administration; additional treatment options include timed light exposure, strategic scheduling of sleep, hypnotic administration, stimulant administration, and/or maintaining home-base (local) sleep hours during short-trips where adaptation would be limited. It is helpful to divide recommendations for travelers into strategies that can be implemented prior to travel, during travel, and at the destination (Table 7.4.2; Figure 7.4.1).

Table 7.4.2: General tips for managing jet lag

Planning

- Choose a flight that arrives at a time that gives the traveler the optimal amount of timed light exposure

- Consider use of a jet lag calculator to personalize recommendations on the timing of bright light, avoidance of light, and administration of melatonin

Pre-flight

- If possible, adjust sleep time to more closely match the sleep period at the destination for a few days prior to the trip

During flight

- Time activities (e.g., meals, sleep, light exposure) based on the destination time zone

- Stay hydrated because volume depletion can worsen physical symptoms of jet lag; avoid excess alcohol

- Avoid sedative medications with long half-lives

Post-flight

- Maximize natural light exposure at the destination

- Avoid lengthy naps during the day at the destination because this will make it more difficult to sleep at night; short naps may improve alertness

Figure 7.4.1

Adapted from the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR) Sleep Research Center.

Strategies for managing jet lag disorder

Strategic shifting of sleep

Adaptation to the destination time zone may be facilitated by shifting sleep toward the destination time zone in the days prior to the trip. For example, shifting sleep 1 hour later (for westward travel) or earlier (for eastward travel) per day in the 2–3 days prior to the trip may reduce the amount of time required to adjust to the destination time zone. Sleep loss during travel can worsen the symptoms of jet lag. Sleep in-flight can be maximized by minimizing alcohol consumption (which tends to reduce sleep latency but increase sleep fragmentation) and caffeine intake. Alcohol and caffeine can also both cause dehydration, which can further exacerbate jet lag. Upon arrival to the destination, staying awake during the local day will increase the homeostatic drive for sleep and help facilitate sleep during the local night. Short daytime naps (20–30 minutes) can be utilized to help sustain alertness during the local day, while longer daytime naps may interfere with subsequent nighttime sleep.

Timed light exposure

Intentional light exposure (or avoidance of such light exposure) at appropriate times of day can help facilitate circadian adaptation to the destination time zone. Light helps to synchronize the internal biologic clock to the environment even in the absence of travel. When crossing time zones, light can play a key role in decreasing the duration of circadian desynchrony. Exposure to bright light in the morning following the circadian nadir (approximately 2–4 hours prior to habitual wake time) promotes phase advances (i.e., it shifts the system earlier and can facilitate going to sleep and waking up earlier), while exposure in the evening generally promotes phase delays (i.e., it shifts the system later and can facilitate going to sleep and waking up later). The optimal timing for light exposure is based on the direction of travel and the number of time zones crossed. Consider using a jet lag calculator (see Jet Lag Calculators section below) for individualized recommendations. Appropriately timed light exposure in combination with melatonin may further facilitate adaptation.

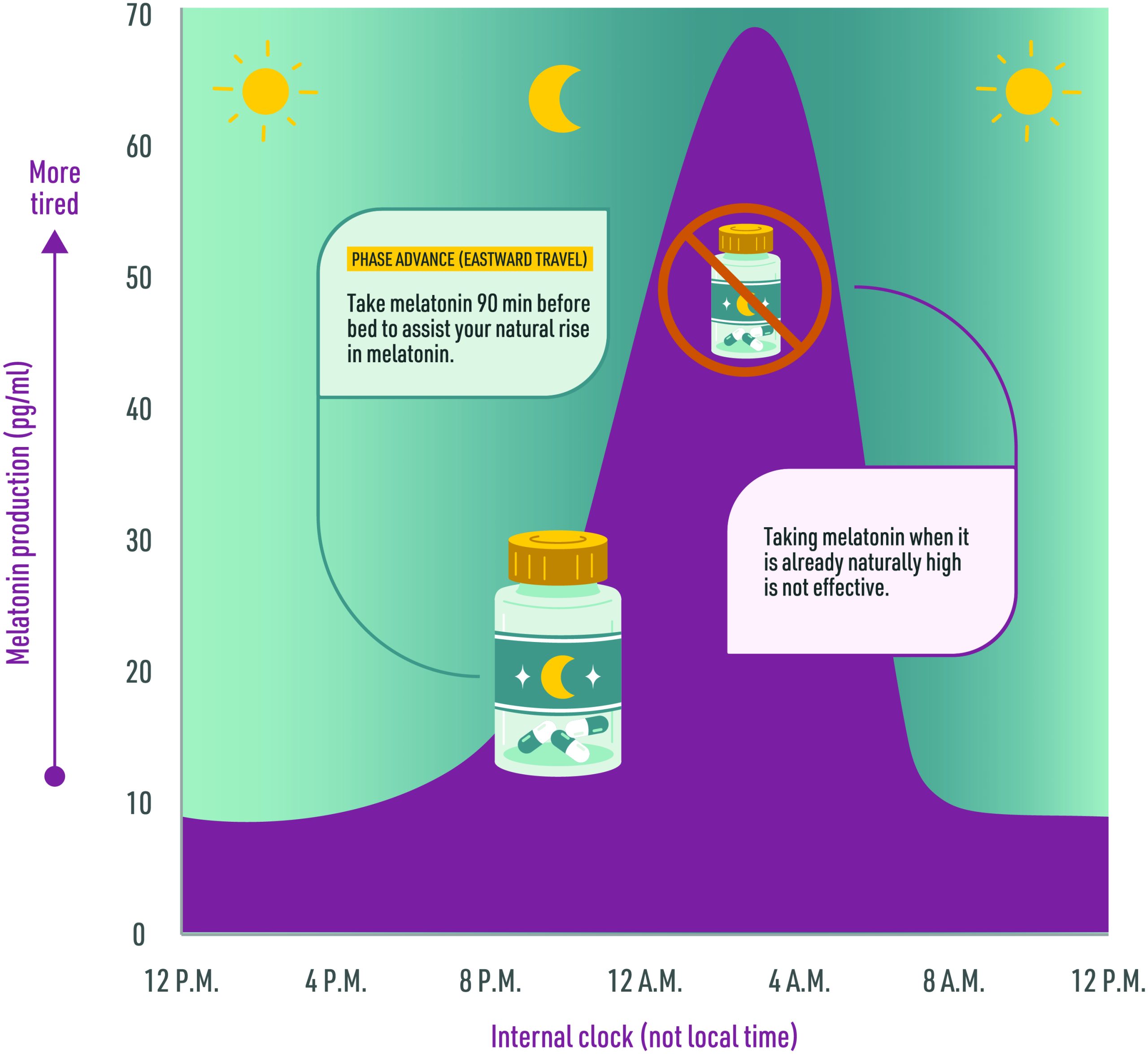

Timed melatonin

Melatonin is secreted by the pineal gland in the brain during darkness and it is suppressed during the day with light exposure. Under a typical sleep-wake schedule without rapid travel across time zones, melatonin is secreted for approximately 12 hours at night—melatonin secretion starts to increase in the early evening about 2 hours before normal bedtime and peak plasma concentration occurs at approximately 3–4 a.m. (Figure 7.4.2). If a traveler takes melatonin when their internal clock thinks it is morning, this will result in a phase delay which can facilitate adaptation to westward travel. Taking melatonin when the internal clock thinks it is early evening will result in a phase advance which can facilitate adaptation to eastward travel. It is important to appropriately plan melatonin as taking it at the wrong time can increase misalignment. In addition, taking melatonin when endogenous melatonin is high (body clock time 12–5 a.m.) is not as effective. Melatonin dosages vary, but 0.5–1 mg is often sufficient to produce a circadian shift. It is not recommended to take high-dose melatonin (>5mg) because this can cause excess melatonin to be present at the wrong time of day as it is metabolized. A note of caution, however, because melatonin is not regulated by the Food and Drug Administration, there is the potential that the amount of melatonin may vary from what is printed on the label. Similar to timed light exposure, recommendations on timing and duration of melatonin for eastward and westward flights is based on the number of time zones crossed. Jet lag calculators often offer recommendations on melatonin usage based on trip schedules.

Figure 7.4.2

Adapted from the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR) Sleep Research Center.

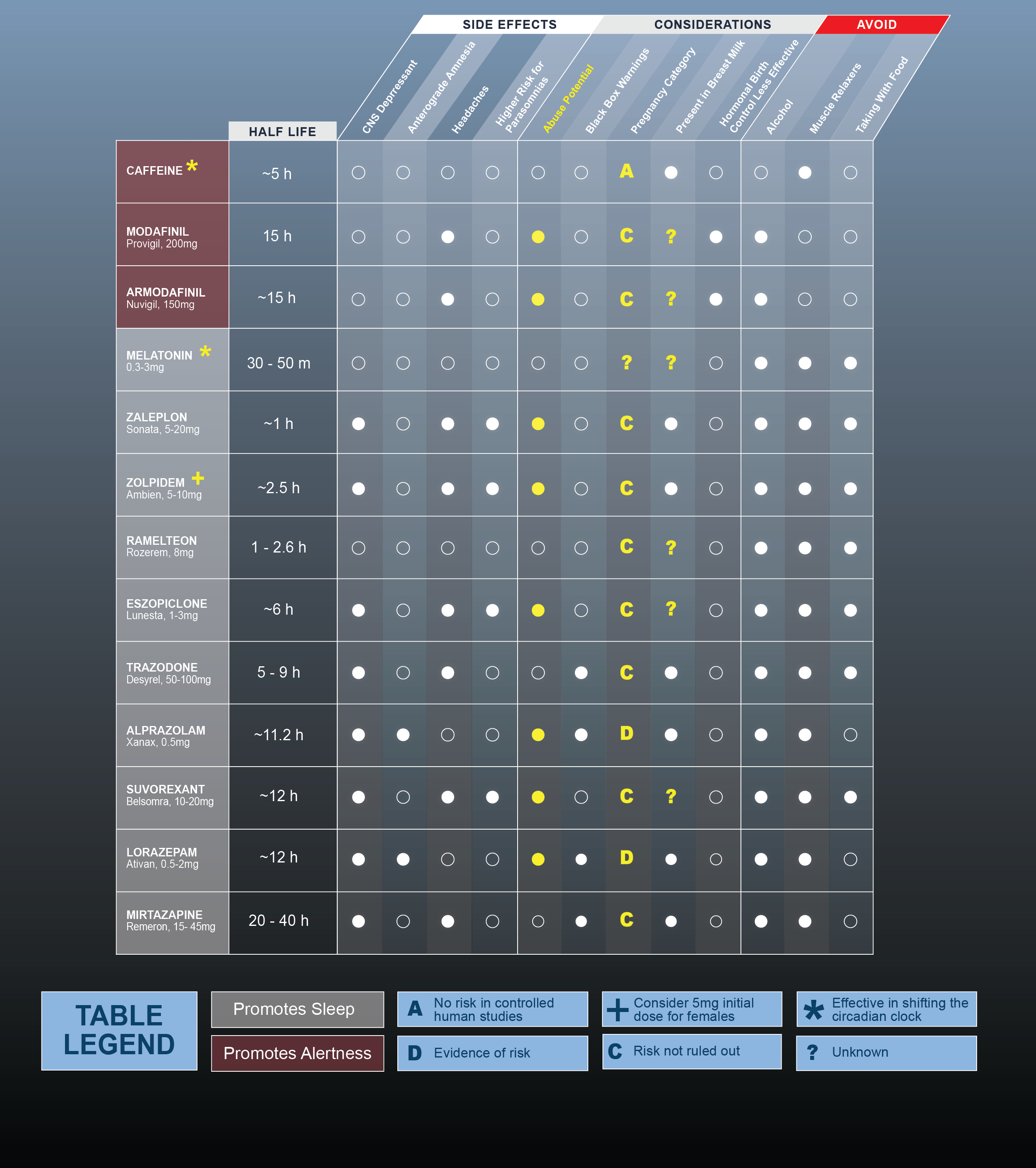

Hypnotics and stimulants

There are several over-the-counter and prescription medications that are often used to help sustain alertness during the local day, promote sleep during the local night, and ultimately adjust to the new time zone. Caffeine and modafinil, for example, are often used to help promote wakefulness and sustain alertness during the biological night. It is important to be mindful of their half-lives which are approximately 5 hours and 12 hours, respectively. Use of these stimulants in the hours before bed should be avoided so as not to interfere with subsequent nighttime sleep. Hypnotics such as zolpidem and eszopiclone are options for treatment of jet lag disorder as outlined in the previously noted AASM report, but the half-lives of these drugs and their possible adverse effects should be considered before use (Figure 7.4.3). Antihistamines, long-acting benzodiazepines, and long-acting benzodiazepine receptor agonists should be avoided as they can worsen cognitive impairment, increase risk of falls, impair physical performance, and have gastrointestinal side effects.

Figure 7.4.3

Adapted from the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR) Sleep Research Center.

Notes

The medications listed are not specific to the treatment of jet lag disorder.

Jet lag calculators

Jet lag calculators have been developed to provide travelers with recommendations on how to mitigate jet lag by adjusting the timing of sleep, light exposure, caffeine consumption, or use of melatonin in the days prior to, during, and following the trip. Light exposure and melatonin recommendations used by these jet lag calculators are often based on phase-response curves. See Figure 7.4.4 for an example of a jet lag calculator using a sample trip from Los Angeles to London, leaving at 5 p.m. on day 1 and arriving at 11 a.m. on day 2.

Disclaimer: Material has been reviewed by the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research. There is no objection to its publication. The opinions or assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the official position of the Department of the Army or the Defense Health Agency.

Figure 7.4.4

- Burgess, H. J., Sharkey, K. M., & Eastman, C. I. (2002). Bright light, dark and melatonin can promote circadian adaptation in night shift workers. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 6(5), 407–420.

- Hilditch, C. J., & Fischer, D. (2023). The Handbook of Fatigue Management in Transportation, Jet Lag, Sleep Timing, and Sleep Inertia (1st ed., pp. 194–213). CRC Press.

- Janse van Rensburg, D. C., Jansen van Rensburg, A., Fowler, P. M., Bender, A. M., Stevens, D., Sullivan, K. O., . . . Botha, T. (2021). Managing travel fatigue and jet lag in athletes: A review and consensus statement. Sports Medicine, 51(10), 2029–2050. https://www.doi.org/10.1007/s40279-021-01502-0.

- Morgenthaler, T. I., Lee-Chiong, T., Alessi, C., Friedman, L., Aurora, R. N., Boehlecke, B., . . . Zak, R. (2007). Practice parameters for the clinical evaluation and treatment of circadian rhythm sleep disorders: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Report. Sleep, 30(11), 1445–1459. https://www.doi.org/10.1093/sleep/30.11.1445.

- Rigney, G., Walters, A., Bin, Y. S., Crome, E., & Vincent, G. E. (2021). Jet-lag countermeasures used by international business travelers. Aerospace Medicine and Human Performance, 92(10), 825–830. https://www.doi.org/10.3357/AMHP.5874.2021.

- Simmons, E., McGrane, O., & Wedmore, I. (2015). Jet lag modification. Current Sports Medicine Reports, 14(2), 123–128. https://www.doi.org/10.1249/JSR.0000000000000133.

- UN Tourism. (2020). International tourism growth continues to outpace the global economy. UNWTO.org. https://www.unwto.org/international-tourism-growth-continues-to-outpace-the-economy.

- Walter Reed Army Institute of Research. WRAIR training and information products. WRAIR.Health.mil. https://wrair.health.mil/Biomedical-Research/Center-for-Military-Psychiatry-and-Neuroscience/CMPN-Training-Products/.